Kentucky Bourbon War Looms Over Technology

There’s a battle coming to Kentucky, and bourbon could soon be more about the test tube than the barrel.

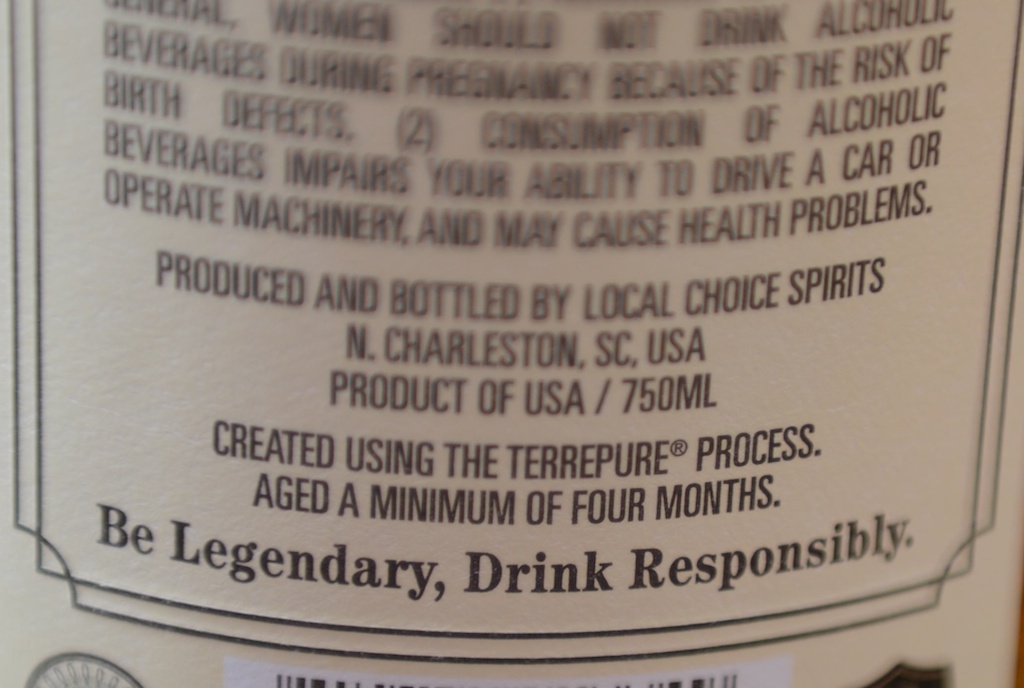

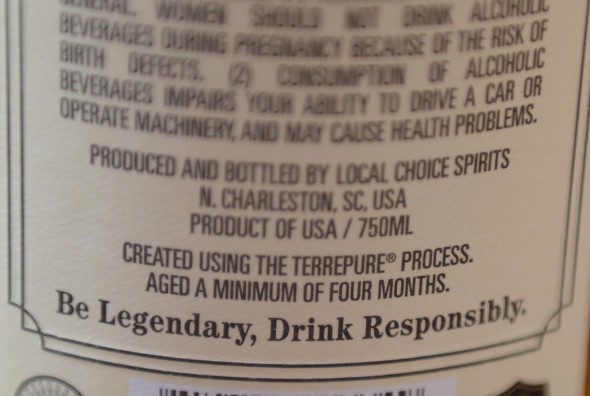

In the next year, a Kentucky bourbon brand will be created using Terressentia’s TerrePURE technology that takes whiskey less than a year old and applies “chemistry instead of the oak barrel,” CEO Earl Hewlette told me in an interview for Whisky Advocate. (TerrePURE has been used to make other bourbons, such as Winchester Small Batch “Straight Bourbon,” but not with Kentucky on the label.)

Terressentia purchased the Owensboro Charles Medley Distillery last year for more than $25 million.

Hewlette claims the technology rapidly matures whiskeys to achieve significant color in four- to six-month-old whiskey and favorable taste phenolics. I’ve not seen this process in action, so my understandings are based on interviews.

South Carolina-based Terressentia has produced several whiskey labels, including the recent Hatfield & McCoy. In my interview with Hewlette, he was very clear that he intends to use his technology in Kentucky bourbon for his own brands and for his distillation contracts.

Now that the Kentucky bourbon sourced whiskey market has dried up—it’s harder for Non-Distiller Producers to buy or contract distill “Kentucky Straight Bourbon” from traditional outlets, such as Heaven Hill, Barton and Brown-Forman—NDPs are reaching out to upstart Kentucky distillers for contract distillations. Currently, New Riff and Kentucky Artisan Distillery are contract distilling for several companies, including names as big as Jefferson’s, because the clients want “Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey” on the label. That means, Hewlette will likely pluck a few NDPs who will want to see Kentucky on the label.

“There remains a belief that Kentucky bourbon is a premium bourbon,” he told me. “So, I think to that extent, being able to offer a product that is made in Kentucky ultimately will be considered a premium over non-Kentucky bourbon.”

This week, Earl’s wife, Paula Dezzutti Hewlette, told me her company, Local Choice Spirits, will soon be launching “Baby Boomer Bourbon.” The exact release date was unclear, but it appears the bourbon will be out within a year and uses the TerrePURE technology.

Meanwhile, Cleveland Bourbon and Lost Spirits boast rapid aging technology that have created heated debates over the use technology in American whiskey. Often relying on the good old boy network, the Kentucky bourbon industry has held tried and true to the mantra that many have tried rapid aging before and they’ve all failed. The industry can no longer say this.

Despite my preference of tradition and the old-fashioned way of making bourbon, you cannot deny Cleveland Bourbon and Terresentia have carved out a market for their respective companies. And while I do not care for the Cleveland Bourbon’s over-oaked profile and find the TerrePURE products too hot and grain-forward, people buy them, people drink them, and distillery engineer types want to know more about them.

Thus, the Kentucky industry must decide how to deal with this technology entering the Commonwealth’s bourbon industry. Will they attempt to change the state or federal laws to disallow certain technologies? Will they do a full-court PR press against TerrePURE? Or will they welcome technology with open arms?

I’ve reached out to the Kentucky Distillers Association, which represents the majority of the state’s distillers. Here’s what KDA president Eric Gregory had to say: “We reached out to Terressentia last year in our first membership drive and invited them to become members. I spoke to their leadership last month to get an update on their renovations and encouraged them to apply. Once we receive their application, we will meet with them, tour their facilities and get to know them better – just as we do with any prospective member. I’m sure there will be questions about their process since this is new technology. But the KDA maintains an open membership policy, and we’re always happy to welcome new companies and new ideas to our distilling family.”

That’s a nice politically correct answer from Gregory, but the truth is his membership loathes the technology. But the distillers of yesterday loathed automation in distilleries.

Before he passed away, Elmer T. Lee criticized automation used in the distilleries. (Here’s a great 2006 interview with Lee on WhiskyCast.) The former Old Fitzgerald master distiller Edwin Foote agreed, saying the human senses are more acute than computers. And before them, Stitzel-Weller master distiller Will McGill and Seagram’s research director Dr. E. H. Scofield often debated about the use of science in the 1940s. (Read about the McGill-Scofield debate in my next book, Bourbon Curious.) And before them, early 1900s distillers debated the use of heat cycling in warehouses.

So, my point is, either this TerrePURE technology is a part of the bourbon technology evolution like heat cycling or it will unify all distillers to stop it.

Because once the technology starts putting Kentucky bourbon on the shelf, it’s not going to stop.

Fred Minnick is the author of Whiskey Women and Bourbon Curious.